Share this article.

As educators, we know the impact meaningful conversations have on learning. We know that the more opportunities students have to share ideas, clarify their thinking with others, make mistakes as they are talking, and force themselves to solidify their understanding, the greater probability they have to learn the content or skills at a deeper level. This is metacognition, and it requires learners to examine, externalize, and apply their thinking, such as:

- What it means to learn something,

- Awareness of one’s strengths and weaknesses with specific skills or in a given learning context,

- Planning what’s required to accomplish a specific learning goal or activity,

- Identifying and correcting errors, and

- Preparing ahead for learning processes. (Chick, 2017)

Metacognition is related to the concept of student ownership—a mindset that leads to elevated academic achievement and that teachers can develop in themselves and in their students. It is the critical thinking skills that empower students to think about, question, and communicate new learning in lasting ways. (Zwiers & Crawford, 2011)

The same is true for adult learners. A principal who is utilizing instructional leadership knows that all learning is supported by a question-driven approach for monitoring and offering feedback.

In our article “The 4 Actions of Instructional Leadership,” we defined the actions of instructional leadership in terms of the implementation of an initiative that increases student achievement. We shared the importance of having a thoughtful, detailed plan specific to the curriculum, instruction, assessment, and climate of the initiative. We shared the importance of communicating every aspect of this plan over and over to ensure clarity from all stakeholders.

In our article “Differentiated Delegation: How to Ensure Individual Success for Each and Every Teacher,” we shared the importance of knowing your teachers—their motivation and capacity—and how you will need to differentiate how you delegate the work. Instructional leadership is about supporting teachers to own their role in the initiative.

But this can only happen if teachers are supported to make stronger decisions. They are being asked to make changes in how they do business. They are being asked to explain how they make changes and the decision-making process behind the change. They need to be clear on the changes they are making and the decisions behind those changes. This can only happen if they are supported to build metacognition around their decisions: how they are making them, why they are making them, and the impact these changes are having on student learning.

To that end, a principal utilizing the power of instructional leadership understands that the most effective method to support stronger teachers’ decision making is through a question-driven process.

Telling or asking closed questions saves people from having to think. Asking open questions causes them to think for themselves. (Whitmore, 2017, p. 39)

This method of discourse allows the teacher to own the feedback process by explaining, clarifying, and reflecting on the decisions they are making to implement the actions of the initiative. In other words, it is incumbent on the principal to help teachers become more effective and efficient decision-makers regarding classroom practice by asking teachers how they make decisions and supporting their metacognition through the articulation of their thinking.

The value of this kind of feedback process is in the conversation. As a principal, the goal is clear—to create awareness and responsibility in teachers regarding the implementation of the initiative. What is said and done must reflect that goal. Thus, just demanding that teachers do something is useless. Instead, principals must ask effective questions that drive a thoughtful conversation that allows the teachers to articulate, clarify, question, and solidify the decisions they are making.

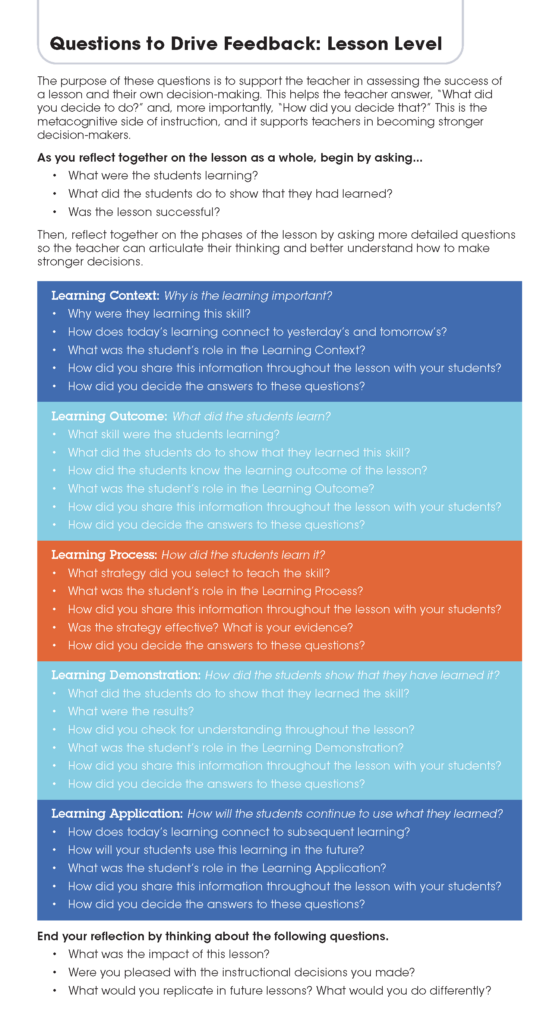

Because the most impactful initiatives are those that focus on increasing student achievement, the most effective way to monitor implementation is to observe their impact on student learning. Thus, the conversation begins with what was observed in the classroom. Questions should begin with broad brushstrokes and then increasingly focus on the details, always eliciting from the teacher the decisions made and the reasoning behind each decision. This questioning for more detail maintains the focus of the conversation.

Below are sample questions that can be used to guide these conversations. We begin with a series of questions to help the principal understand the impact of instruction on student learning at the lesson level. We then offer a series of questions specific to the implementation of individual initiatives. These questions are only a jumping-off point. As John Whitmore (2017) explains,

Questions are most commonly asked in order to elicit information. I may require information to resolve an issue for myself, or if I am proffering advice or a solution to someone else. If I am a [principal], however, the answers are of secondary importance. The information is not for me to make use of and may not have to be complete. I only need to know that the [teacher] has the necessary information. The answers given by the [teacher] frequently indicate to the [principal] the line to follow with subsequent questions, while at the same time enabling him to monitor whether the [teacher] is following a productive track, or one that is in line with the [initiative being implemented]. (p. 41)

Therefore, give yourself the freedom to take the conversation in any direction that allows you to better understand the teacher’s thinking. Remember, the aim of every conversation is not “right” or “wrong” answers, but to have the teacher articulate their decision-making process.

Questions to Drive Feedback at the Lesson Level

We begin our conversation at the lesson level. It is important to first understand what decisions the teacher made regarding the lesson observed. We know from Madeline Hunter (1982) that teaching is a constant stream of decisions made before, during, and after interactions with students. Each lesson must be driven by the learner, the learning outcome of the lesson, and how the learner is supported to own their learning.

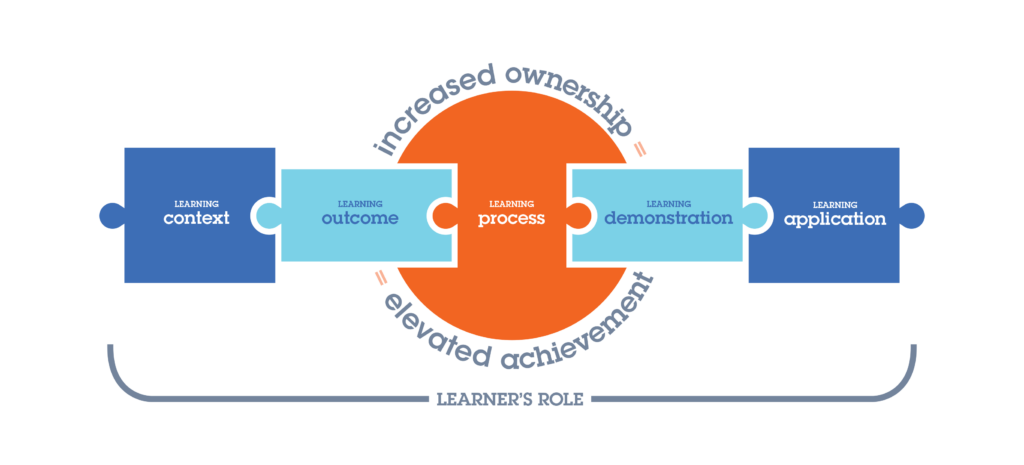

There are five student-centered phases of an effective lesson.

- Setting the Learning Context: Why is the learning important?

- Stating the Learning Outcome: What will the students learn?

- Engaging in the Learning Process: How will the students learn it?

- Producing the Learning Demonstration: How will the students show that they have learned it?

- Implementing the Learning Application: How will the students continue to use what they have learned?

Addressing the five phases by answering these questions during planning and then sharing the information with students before, during, and after a lesson will clarify for them their role in the learning. This, in turn, increases ownership of the learning which elevates achievement. We call this a Focused Learning Model.

Here are questions aligned to the Learning Model that principals can selectively utilize to begin to understand the decisions a teacher made at the lesson level. But please note, even if the teacher did use the Learning Model when planning and/or delivering a lesson, these questions can still be used for effective feedback because they encourage a teacher to articulate their thinking. This is metacognition around the craft of teaching. And this will make them stronger decision-makers for future lessons.

Teachers play a crucial role in ensuring that students receive the positive effects of a well-implemented student-focused initiative. The teacher is the key decision-maker for establishing effective learning design before, during, and after instruction. Because the teacher is the person who knows the most about the students, it is important that the teacher’s ownership in making these decisions is cultivated by the principal.

Continue the Learning

Check out these articles and resources to continue your learning about this topic…

The Learning Brief

In this article you learned…

- Why question-driven feedback is the most effective method to support stronger teachers’ decision making.

- How this method of discourse allows the teacher to own the feedback process by explaining, clarifying, and reflecting on the decisions they are making to implement the actions of the initiative.

- The guidelines for offering question-driven feedback to your teachers.

Can you imagine building an environment full of motivated, engaged, and eager students who own their learning?

We can.